The year 2018 marks the 150th anniversary of Japanese immigration to Hawaii. The Honolulu Festival hosted a few commemorative events.

-The History of Japan and Hawaii-

It is imperative to understand the historical background; how Japanese people related to Hawaii from the first Japanese immigration down to this day. Let’s take a look at a chronological table for a general overview.

- 1850年

- The first sugar cane farm was established by a Caucasian investor. It rapidly grew to be a huge industry.

- 1860年

- King Kamehameha IV proposed a friendship treaty between Japan and the Kingdom of Hawaii. The Japanese ambassadors, Jon Manjiro and Yukichi Fukuzawa, boarded the Kanrin-Maru to visit Honolulu. The King pleaded to send laborers from Japan.

- 1861年

- Civil War broke out in the Mainland U.S.

- 1865年

- Eugene Van Reed, a Japan based American businessman, was appointed Consul General of Hawaii in Japan by the Kingdom of Hawaii. Eugene negotiated with the Edo Shogunate about the recruiting of Japanese immigrants to Hawaii.

- 1868年

- In May, the first year of the Meiji-era, the ship, “Scioto,” departed Yokohama port with approximately 150 Japanese people without permission from the new Meiji Government. The ship arrived at Honolulu port on June 20th.

- 1869年

- About 40 Japanese immigrants were returned to Japan after the Japanese Government sent a special envoy to charge a contract violation.

- 1871年

- Japan and Hawaii entered into a Treaty of Amity and Commerce, and subsequently improved the treatment of Japanese immigrants.

- 1876年

- The Reciprocity Treaty eliminated all tariffs on sugarcane export. The kingdom of Hawaii became one of the leading sugarcane exporters.

- 1885年

- The Convention of Japanese Immigration Treaty was signed, establishing immigration recognized by the Japanese government.

- 1894年

- The 1885 Convention of Japanese Immigration Treaty agreement was terminated. The Japanese government turned immigration operations over to private companies.

- 1898年

- The United States annexed the Kingdom of Hawaii, bringing the end of contract labor. Japanese plantation workers were freed from labor contracts.

- 1902年

- Seventy percent of sugarcane plantation workers were Japanese immigrants.

- 1908年

- The Gentlemen’s Agreement took effect. Private companies no longer managed immigration matters. The agreement restricted Japanese immigration to the United States. Only Japanese who had previously already emigrated to the US, and their immediate relatives, could now enter the country.

- 1920年

- Japanese workers joined organized major labor strikes, demanding improved work conditions. The Japanese plantation work force plummeted to 19 percent.

- 1924年

- The US Congress passed the Asian Exclusion Act, which barred East Asians from immigrating to the country. By that time, there were 21,000 Japanese immigrants living in Hawaii.

- 1941年

- Pear Harbor was attacked by Japanese military forces, which led to the U.S. entry into WWII. About 400 Japanese Americans in Hawaii were relocated to internment camps.

- 1942年

- The Nikkei (second generation of Japanese Americans) volunteered and became members of the 100th Infantry Battalion and after training, were sent to European front.

- 1944年

- The 442nd Regimental Combat Team was formed and sent to the European front.

- 1945年

- Germany surrendered. The Pacific War ended.

- 1952年

- The passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act enabled the Issei (first generation of Japanese Americans) and other Asian American immigrants to become naturalized U.S. citizens.

- 1959年

- Hawaii became the 50th state of the United States from a U.S. Territory.

- 1988年

- The Civil Liberties Act of 1988 was signed into law, and a payment was authorized to each WWII internment camp survivor.

- 2016年

- The 75th anniversary of the Pearl Harbor Attack. Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe visited Pearl Harbor.

- 2018年

- The 150th anniversary of Japanese Immigration to Hawaii

Initially, increasing demand for labor at sugarcane plantations made it difficult to find enough laborers within the Kingdom of Hawaii. The kingdom established contracts with many foreign governments in order to gain an immigrant work force. Approximately 220,000 Japanese people migrated to Hawaii until the Asian Exclusion Act took place in 1924. Many immigrants remained in Hawaii after their contracts expired, and blended into and became contributing members of the society. The Issei and the following generations’ efforts as Japanese-Americans, built a firm foundation in the society of Hawaii.

The locals called the first Japanese immigrants of 1868, “Gannen Mono” (people of the first year in the Meiji period).

During that time, Japan was going through the Meiji Restoration, a transfer of power from the Edo Shogunate to the Meiji Emperor. Permission of Japanese emigration was obtained from the Edo Shogunate. However, the new Meiji Government that came into power, nullified all the Edo Shogunate’s treaties. Van Reed, Consulate General of Hawaii, nevertheless, proceeded without the new government’s permission to send Japanese to Hawaii. The first immigration was carried out illegally without government permission.

The “Gannen Mono” suffered grueling labor conditions on sugar plantations. Different from what they had previously heard back in Japan, it turned out to be a “slave-like” treatment by the plantation owners. The immigrants, however, endured the inconceivable hardships, settled in the land, and raised their families. As a result, the population of Japanese Americans in Hawaii increased dramatically.

After the start of WWII, many Japanese Americans living in the United States were rounded up and removed to internment camps. Smaller numbers of Japanese Americans in Hawaii, compared to the U.S. mainland, were relocated to internment camps, partly due to the large Japanese population in Hawaii and the limited space in the internment camps. By that time, the Japanese immigrants and their descendants had become an important part of the society. We are what we are today because of the perseverance of the “Gannen Mono” and the subsequent Japanese immigrants.

-Eishokukai Presents a Katari Butai (Narrative Theater) – Japanese Immigration to Hawaii and Invitation to Japanese mythology-

In commemoration of the 150th anniversary of Japanese Immigration and the “Gunnen Mono”, the Honolulu Festival hosted a Katari Butai to memorialize the origin of Japanese immigration.

The Narrative Theater began as a project to narrate “Kojiki (the records of ancient matters)” and “Nihon-shoki (the oldest chronicles of Japan)” at shrines in Japan. The “Japan Mythology Telling Project” started in 2003 at the Ise Shrine and Izumo Taisha by Eishokukai, a national voluntary group consisting of shinto priests.

The narrative theater happened once before in Hawaii, but this time, it took place at the150th Anniversary event. They were curious, “How the local audience would respond to all-English narratives?”

Frank Delima, a comedian with a 44 year career in the entertainment industry, hosted the event with humorous talk, even inserting singing Japanese children’s songs.

The Japanese mythology narrator was Cathy Foy, an actress who has performed on Broadway. Yasu Ishida recounted Japanese immigration in Hawaii. Joshua Kei provided sound effects with his keyboard during the narration.

The program titles were “Japanese Immigration, A Bridge to the Rainbow,” and “Yamata No Orochi (eight-headed-creature).” The scripts were written by Sosuke Kinoshita and translated by Machiko Izumi, who also translated scripts for the Super Kabuki overseas performance.

The first narrative, Japanese Immigration Story, “A Bridge to the Rainbow,” is about “Gunnen Mono,” the first 150 immigrants who traveled to Hawaii in 1868.

Yasu Ishida recounted the first immigrants and how they lived in Hawaii.

Story of A Japanese Immigrant “A Bridge to the Rainbow”

In 1885, Masakichi Yasumura, a single man, came to Hawaii along with 944 other Japanese people, an immigration recognized by the Meiji Government. He was 20 years old from Yokohama, and determined to succeed in the land of Hawaii. He was fired recently from his job in Nipponbashi which he had held since 15 years old. Then, he learned about labor recruitment in Hawaii.

Masakichi saw a rainbow in the beautiful sky and uttered, “What a big rainbow! This must be a welcoming sign from Hawaii!” Masakichi’s heart was filled with hope and excitement.

Masakichi came to Hawaii as a laborer at a sugar plantation. What awaited Masakichi there, however, was a life of struggles and grueling labor. Feeling betrayed and disappointed, Masakichi cried out, “What did I get myself into!” Masakichi nevertheless, endured the hardship and determined to succeed, ”I will never give up. I will make it through!”

Masakichi’s story gives us a vivid picture; what was like to live as a plantation worker. No matter how grim the situation seemed, Masakichi stayed on track, dreaming, getting married to Suzu, and the birth of his son. He enjoyed many joys and overcame various obstacles with determination, including losing his beloved son to illness.

The grueling labor conditions at sugar plantations eased when a political transformation took place in Hawaii. The U.S. annexation of Hawaii brought better work conditions for laborers. Consequently, the nisei (second generation of Japanese Americans) and sansei (third generation of Japanese Americans) settled down in the land.

The situation changed dramatically when WWII broke out. Hawaii was attacked by Imperial Japan, and the Japanese Americans in the U.S. faced the harsh reality of being ethnic Japanese. Various persecutions included incarceration of Japanese Americans in internment camps. Despite such dismal circumstances, the Japanese Americans volunteered in the Army and became members of the 100th Infantry Battalion, the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, and the Military Intelligent Service. Their remarkable service was recognized with the highest achievements in U.S. military history. They were honored with many military successes and medals.

It all started when the “Gannen Mono” left their native land and came to Hawaii as immigrants. The following niseis and sanseis, while being ethnic Japanese, proved their identity as Americans through their loyalty to the U.S.

Unfolding the history of Japanese immigration makes one wonder: What is a home country, What is an ethnicity, What is the land of your youth, and What is peace?

Yasu Ishida concluded, “We owe our existence to the earlier immigrants. What they have built, as a result of their tremendous hardships and sacrifice was, “A Bridge to the Rainbow.”

Actress, Cathy Foy narrated the story, “Yamata no Orochi” from Japanese mythology.

Japanese Myth “Yamata No Orochi”

Similar to Japan, there are many gods in Hawaiian mythology: “Kū” is the god of war, “Pele” is the goddess of fire, “Lono” is the god of agriculture and peace, and “Kāne” is the god of procreation.

A majority of Japanese myths are found in the “Kojiki”, “Nihon-shoki”, and “Fudoki”. Japanese gods were worshiped at shrines from ancient times.

Hawaii has its own Izumo Taisha. Izumo Taisha in Japan worships Okuninushi no kami (god). Susanoo, an ancestor of Okuninushi, was kicked out of takamagahara (heavens) and descended in Izumo no kuni (county of Izumo). “Yamata no Orochi” is a story about Susanoo’s adventure.

The story is told that Susanoo met an old couple and their daughter in the county of Izumo. Hearing their plight that the daughter was about be eaten by Yamata no Orochi, a huge snake with eight heads and eight tails, Susanoo agreed to fight the snake under one condition; if he won, the daughter would become his wife.

The audience’s eyes were glued to Cathy’s realistic portrayal of Susanoo, being forced out of the heavens. Cathy, as Susanoo, cried out desperately to see Izanagi (god).

When Susanoo transformed Princess Kushinada into a comb and stuck it to his head, Cathy used her own accessary to demonstrate. The audience was carried away in their imagination as each scene unfolded, as if listening to a radio drama.

At the end of the story, Susanoo read a poem, “Yakumo Tatsu Izumo Yaegaki Tsumagomini Yaegaki Tsukuru Sono Yaegakio (“Actively upwelling clouds covered the eightfold fence in Izumo. It makes the eightfold fence to have my new wife stay in the house. Great eightfold fence.”) This poem is known to be Japan’s oldest poetry.

The two narratives teach us respectively the importance of: celebrating the lives of brave Japanese immigrants who traveled to an unfamiliar land of Hawaii, and taking pride in the heritage of Japanese mythology and passing it on to the following generations.

This time the audience was made up of largely elderly people. Next time, we would like to invite local children and give them a chance to hear the narratives. They will surely be impacted by the stories.

-Sakurakomachi Wagakudan ~Hawaii Tour 2018~ ”Singing the Heart of Japanese”-

Sakurakomachi Wagakudan is an all-female orchestra. It plays traditional Japanese music and folk songs, using instruments such as koto, Tsugaru-shamisen, shinobue and wadaiko. As an orchestra consisting entirely of women from Japan, they strive to create inspirational art and entertainment. The members are active internationally and perform all over the world every year.

~Koto (Japanese harp)~

The prototype of koto was imported from mainland China during the Nara period. The instrument then evolved to play a wide variety of songs during the Edo period, leading to its popularity across Japan. Koto has 13 strings, and performers alter the pitch of a string by manipulating the string tension.

~Tsugaru shamisen~

Tsugaru shamisen was established as a genre in the Tsugaru region of western Aomori. It is characterized by a unique, percussive playing style, and its repertoires of songs with faster beats and tempo.

~Wadaiko~

This instrument is widely played at festivals, kabuki theaters, and ceremonies in temples and shrines. The wooden body of a drum is covered with leather skin, and strokes on the skin produces powerful sounds.

~Shinobue~

Shinobue is a general term for Japanese transverse flutes made out of bamboo with holes cut into them. The instrument has long been used for various genres of music, such as Japanese folk songs and nagauta ensembles. It is one of the most familiar musical instruments for Japanese people.

The all-member orchestra opened the program with “Sakura, Sakura (cherry blossoms),” while the audience sang along with.

The following numbers were “Haruno Umi (spring oceans),” creating a new year like atmosphere, and “Tori No Yoni (like a bird)” with powerful koto playing.

Taiko and shinobue duet played celebratory “Kotobuki Jishimai (celebration lion dance),” followed by “Tsugaru Jongara Bushi (fork song)” by Tsugaru-shamisen.

While the audience joined in with the shouts “Hoy, hoy,” the Wagakudan members sang an Aomori bon dance song. Volunteers had a chance to try playing wadaiko.

Shouts from the audience conjointly with wadaiko, led up to its climax; singing “Ueo Muite Aruko (English title, Sukiyaki),” uniquely accompanied by the Japanese instruments to wrap up the program.

Japanese immigrants would sing songs and play music to ease their pain and gain momentary relief while working in harsh environments. People were reminiscent of their homeland, friends, and families, and gained strength to live on while playing and singing songs. We realized how precious Japanese musical instruments were to Japanese plantation workers.

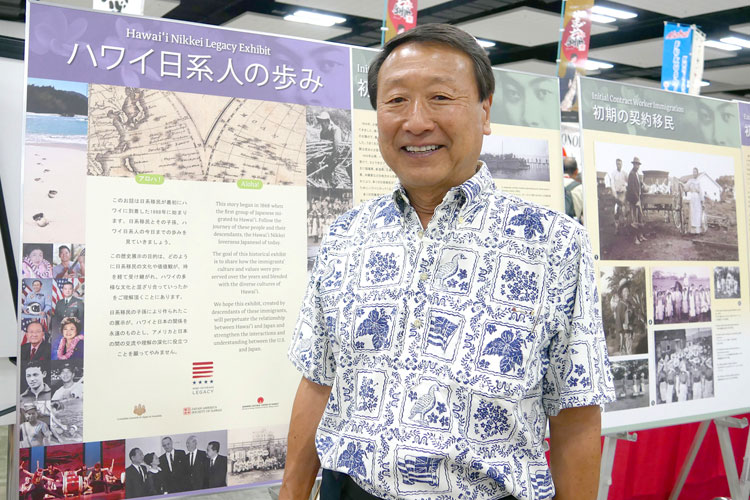

-Hawaii Nikkei Legacy Exhibit-

Pictures were on display at the Hawaii Convention Center, covering the history and culture of Japanese Americans in Hawaii.

The exhibit was a part of the Educational Program in support of the sub-theme “Harmony over the Ocean, Journey to Peace.” Many people stopped by at the exhibit and were looking at each panel very carefully, one by one.

There was a message written on the first exhibit, which read, “The exhibit covers from 1868 when the first Japanese immigrants arrived in Hawaii, the lives of the Japanese immigrants and their descendants, till today. The historical exhibit seeks for visitors to understand how culture and values were transferred beyond time, while mingling with various cultural influences in Hawaii

There was a message written on the first exhibit, which read, “The exhibit covers from 1868 when the first Japanese immigrants arrived in Hawaii, the lives of the Japanese immigrants and their descendants, till today. The historical exhibit seeks for visitors to understand how culture and values were transferred beyond time, while mingling with various cultural influences in Hawaii.

The descendants of Japanese immigrants made the exhibit possible. We hope the relationship between Hawaii and Japan continue to thrive, furthermore, deepening relationships and mutual understanding between America and Japan.

The photo exhibit was shown in several locations in Japan in 2017 with warm responses from the Japanese public. The narrative text and captions are in Japanese and English.

In 2018, the exhibit is planned to be shown around the State of Hawaii jointly by the Nisei Veterans Legacy and the Japan Consulate of Honolulu as part of the 150th anniversary celebration of the initial Japanese immigration to Hawaii. The Honolulu Festival will be its first venue in Hawaii.

Mr. Barns Yamashita, a member of Hawaii Nisei Veteran Legacy, was an instrument to bring the Nikkei Panel Exhibit to the Honolulu Festival.

The exhibit begins with the arrival of the first Japanese immigrants in the late1800s, then continues to show how the Japanese and the Hawaiian cultures were woven together and constructed a modern society. There is a list of prefectures, with short descriptions, of the birthplaces of prominent Japanese Americans in Hawaii and their ancestors.

The exhibit seeks to display the legacy of Japanese Americans in Hawaii and furthermore, promote friendly relationship between Japan and America by deepening the understanding of their differing cultures and traditions.

Guided-tours were offered on the 10th and 11th, both in Japanese and English at different time schedules. Mr. Masakazu Asanuma, a resident of Hawaii for 27 years, has been engaging in the Japan-Hawaii cross-cultural activities. He shared many episodes relating to Japanese immigration.

Mr. Masakazu Asanuma is actively involved in many Japan-America cultural exchange programs.

The below are some tidbits:

- The first group of Japanese immigrants from Yokahama were rather inexperienced in agriculture.

- The ship with the first immigrants on board sailed the ocean for one month until its disembarkation at Honolulu port, compared to seven days today.

- Under the contracts legally recognized by the Japanese government, the four largest immigration groups were from Hiroshima, Yamaguchi, Kumamoto, and Fukuoka. Seventy-four percent of all immigrants were from Hiroshima and Yamaguchi.

- Reasons for large immigration numbers from Hiroshima and Yamaguchi involve: Yamaguchi was a home prefecture of Foreign Minister Kaoru Inoue, who actively recruited applicants, and those unable to pay taxes, due to a land tax reform, were offered the option to work away in Hawaii.

- On the contrary, the prefectures with the least numbers of immigrants were Nara and Kyoto.

- The immigrants, who came as single men, married “picture brides.” Picture brides were young Japanese women who came to Hawaii to marry men they only knew in photos.

- An old Japanese school building still exists on Campbell Avenue in Kapahulu.

- At the time of the Pearl Harbor Attack, the number of Japanese American in Hawaii was approximately 160,000, about 40 percent of the population.

- The 100th infantry battalion, a Japanese American infantry unit, was composed of former members of the National Guard. The 442nd infantry regiment was an all-volunteer force. The U.S. Army called for 1,500 volunteers from Hawaii and an overwhelming 10,000 men (more than 6 times) volunteered.

- The Nikkei soldiers’ bravery earned more than 9,400 Purple Hearts, an award given to those wounded or killed while serving. The 100th Battalion’s high casualty rate earned the most Purple Hearts in the U.S. military.

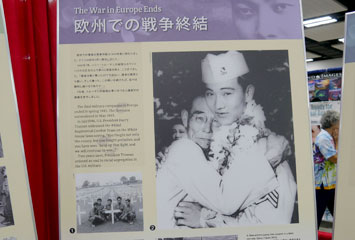

Here are the most impactful photos in the exhibit:

A father’s expression of relief reflects the tumultuous time, as he hugged his son who just returned safely from war.

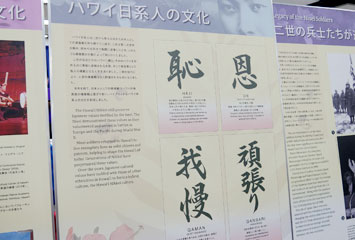

The Nisei soldiers went to war as Americans, while firmly holding onto their Japanese values.

“On (debt of gratitude)”, “Haji (shame)”, “Gambari (tenacity)”, “Gaman (endurance)”, “Gisei (sacrifice)”, “Giri (obligation)”, “Meiyo (honor)”, “Sekinin (responsibility)”, “Houkou (service)”, “Kansha (gratitude)”, “Hokori (pride)”, and “Chugi (loyalty)” These words particularly resonate with Japanese people’s conscience as uniquely Japanese virtues.

Nisei soldiers fought the war with values planted in their hearts by the issei generation. Those values, with the passing of time, were gradually interwoven with other ethnic values in Hawaii, and consequently formed a hybrid culture in Hawaii.

Although the immigrants’ lives were full of adversity and further exacerbated by the war, the issei and nisei people, through the tumultuous time, continued to embrace the concept, “Okage Sama De, meaning, “I am what I am because of you.”

The issei immigrants and the U.S.-born nisei, were guided by many Japanese and non-Japanese people, groups, and leaders. They concluded, “We are grateful for being a member of the society in Hawaii. We are what we are because of you.”

We owe to the issei and the nisei; today we thrive in Hawaii because of their influence in Hawaii throughout generations.

The 150th Anniversary events presented visitors the opportunity to deepen their understanding of the history of immigration. The Japanese Americans will continue to be an essential part of the society in Hawaii. Likewise, the Honolulu Festival seeks to play its role to advocate world peace, with the mission of building love and trust among nations, by introducing Japanese virtues and values throughout the world.

日本語

日本語